|

|

|

|---|

Watch the episode here

Listen to the podcast here

Download “The 10 Best Things To Know About Venture Debt” from https://7in7show.com/.

Kelly Perdew is the Co-Founder and Managing General Partner of Moonshots Capital. Kelly shares his journey from high school in Wyoming to West Point, his military service, and his transition into entrepreneurship and venture capital. He highlights Moonshots Capital’s focus on investing in extraordinary leadership and how military veterans often bring valuable qualities to the business world.

In this episode, Zack and Kelly discuss:

- Mastering Media: Lessons from Working with Donald Trump on The Apprentice

- Smart Funding: Extending Startup Runway to Ensure Survival

- Startup Survival: Outrunning the Bear and Navigating the Valley of Death

- Unlocking Growth Potential: How Venture Debt Fuels Startup Success

- A Decade of Dedication: How Reputation Powers Investment Success

- From Battlefield to Boardroom: The Unique Strengths Veterans Bring to Startups

- How Military Bonds Shape Game-Changing Venture Investments

From Star Apprentice To Leading Venture Capitalist With Kelly Perdew, Managing General Partner, Moonshots Capital, Part 2

Big Picture Of VC Themes

This is part two of my episode with Kelly Perdew, the Cofounder and Managing General Partner at Moonshots Capital. We should shift gears now and talk about some of the seven key questions. I feel like we could talk about all these other things all day long. It’s been great talking about all this stuff, but let’s dig into the big picture of VC themes. I want to start with trends that you’re seeing in venture capital and what you’re seeing in the innovation space in general. A lot of it is a challenge right now, frankly, but let’s dig into the big-picture themes.

Clearly, at least from the VCs that I’ve been operating and how we’ve operated, a pendulum swinging from growth at all costs back toward what we’ve always been grounded in is you have to actually build a real business. That’s got compelling margins and real sales motion that you understand. The CAC to LTV has to be appropriate for the business you’re building. When we invest, again, hurling seed stage, pre-pandemic, we required a pro forma that we would scrub hard and still showed that with the round we were investing in, we would get 18 to 24 months of runway.

We were late seed, so there’s approaching $1 million in annual recurring revenue, which ultimately meant that 18 to 24 months after taking this round of financing. When you’re already close to $1 million annual recurring revenue, you will either have executed operational metrics that support another round of financing or we could cut the cost, cut the burn, or you’re not going out of business just because you raise a round right now. That saved all of our companies from going under during the pandemic, that discipline and mentality about how we were approaching that fundraising.

For us, that’s gone to 36 months now because the distance between a seed and an A has gotten a lot farther apart and a lot harder to hit all the milestones in order to win that deal. I also believe in the same way that there’s going to be a bunch of companies that don’t make it a higher percentage of companies that don’t make it to A in this next 3-year time span than there were in the previous 10 years. I think a lot of the thousand-plus VCs that raised their first fund over the last few years are also going to have the same problem.

There wasn’t significant discipline. There wasn’t an understanding about how to invest, and it was a cool thing to do to be a VC. It’s very difficult to be a VC, especially early stage, if you’re looking for any short-term signals or indicators. You don’t know if you’re even close to good for a 5-year to 7-year time frame. Typically, it doesn’t mean there are aberrations. I like to joke it’s a hopefully get rich slow scheme. It is not a get-rich-quick scheme. For that type of perseverance, you have to have significant passion about what you’re doing.

Fundamentally, for Craig and I, the thing that we’ve added to our context on how we make decisions on founders, two things that aren’t listed on the website that are criteria. When we get off with that founder, we’re both, “F*** yeah,” like, we have to do this deal. That’s one. I don’t know how you completely articulate that with numbers. Two, very importantly, the company has to be meaningful.

On the current trajectory for what they’re doing, it has to do something for the world, i.e., it’s not a horoscope company. Not that that doesn’t do things for the world, but it’s much more along the lines of our dual use focus where we’re doing things that increase equity in the ecosystem like ID.me does for people who previously weren’t able to show who their identity was or what Red6 is doing with making the world safer by training up us pilots and protecting what we’re doing here. F*** yeah and meaningful have become super important to us.

I love those points. I’ve been very disappointed with the VC ecosystem over the last couple of years in the sense that I think there’s just been a lot of crap that’s been funded. People just come up with ideas that aren’t actually solving a problem. There’s like, “I’m copying this business model,” trying to tweak it on the margins. The reality is when we talk about getting back to basics, to me, it’s not just, “Let’s find a company that reaches profitability sooner.”

It’s, “Let’s solve some real problems that add real value.” It’s like enough of the BS. Can we please just go find some companies that can solve some real problems that make our lives better? There are not as many out there as you might think, but the ones that are, are going to be the ones that are successful, in my view. The other thing I’ll add is I think liquidity now, having a strong runway, a long runway, is imperative, like you talked about. I actually think that’s going to be the primary differentiator between companies that are successful and those that aren’t over the next three years.

What I mean by this is that you can take like 3 or 5 companies that have similar business models and similar products, if you will. The one that’s going to survive and ultimately win and capture that market is the company that has the most capital because the others are simply going to run out of capital or it’s going to be too expensive for them to raise and it’s going to hamper their growth. You don’t actually need to be the best product in your category.

You could be number 3 or 4 or 5, but if you’re a good marketer and you can raise capital, going back to what we were talking about with Trump and marketing, then you can survive and outlast your competitors. They will literally drop because they will run out of runway. That’s what I’m seeing now. I think that’s going to be the case.

Quite frankly, I think a lot of VCs and startups were slow to get it through their minds that you have to go raise capital now because if you think you’re going to go raise capital when you’ve got six months of runway left, you’re done. You might as well just wrap. It’s a zombie company. Nobody’s going to fund it because every VC with half a brain is thinking like you and I, which is, “I want to see a longer runway right now. I want to see a company that can reach profitability. I want to see a company that’s sustainable and that can last through a recession.”

I described what you just said, you’re going for a walk in the woods with your buddy, and you turn around and the bear is there. You don’t have to outrun the bear. You have to outrun your buddy. It’s absolutely true that understanding how to really extend your runway is job number one for the CEO. You are ensuring there’s gas in the tank to make it to the other side.

Every company that I’ve been involved with has had some type of valley of death where the product’s not quite working, we’re not quite there yet, we need to do a bridge round, and we need our strategic investor to bridge this a little bit further. All of those have gotten to really significant outcomes. All of them that have gotten to really significant outcomes have overcome those challenges or obstacles. You simply cannot run out of money.

Key Investment Principles

What are the key investment principles that you live by?

Venture Capital: You have to actually build a real business with compelling margins and a clear sales motion.

Our focus has been extraordinary leadership. That is the number one criteria. That founder does not have to be a military veteran or Division One team athlete, exemplifying overcoming some extraordinary hardship. We have way over-indexed on what we call non-traditional founders, not just military veterans but also women and people of color. Those last two categories were non-intentional.

It was because we invested late seed and we have literally thousands of deals per deal that we do, if somebody gets through all of those filters, gets up to us and we like it, and it’s a woman or person of color to the point it’s gotten to there, they’ve probably exhibited all those leadership characteristics that we love in military veteran founders. We’re about finding the person that’s going to be able to execute with that extraordinary leadership. That’s the first piece for us that’s the most important.

Craig and I have had fifteen operating roles between us, so across multiple sectors. That company being in a sector that we’re focused on, either through our operating experience and/or investment experience, helps leverage our network and our knowledge. That’s another important criteria for us that we really like to look at. As I said, in addition, we like it to be approaching $1 million annual recurring revenue and a sector that we like. All those pieces. Craig and I have to be compelled because, as I said, this is 7, 10, or 15 years working with these founders. It’s a marriage that we really have to be excited about.

I’m in the shower in the conditioner thinking about, “How do I help ID.me today?” That’s how we want to be fired up about these deals. It’s got to be meaningful. We are probably halfway through fund one. We’re only going to do things that move the needle in a big way for the defense of the United States, the health of humanity, space exploration, or whatever it might be. It really needs to be something that’s truly massive. If something makes it through all those, but we’re excited about it, they’re in the finals for negotiating to try to get a term sheet.

One of the things that you touched on is the backgrounds of people. I’ve been thinking a lot about this idea of track record. I think the track record in terms of numbers is actually overrated. I was reading an article about how some LPs, and institutional investors are questioning whether they want to stay with Sequoia, even though Sequoia’s got, whatever it is, a 40, 50-year track record. My thought was, “Who cares what somebody at Sequoia was doing 40 years ago?” That’s not the person making decisions now.

They’ve got an institutional structure, but that’s like saying, “I would love to do business with Lehman Brothers because they were a great franchise and fixed income for decades.” They’re no longer around, they screwed up. My thinking is that your track record is important, but how you evaluate or what you consider track record is more important. In other words, go find founders who have overcome some incredible obstacles like you talked about. Don’t just show me, “This guy’s got like a good track record working at some generic financial firm that’s got a good brand.”

Who gives a crap? Those guys are a dime a dozen. Find me somebody who’s overcome real hardship. That, to me, is the person I want to bet on. I think there needs to be more time and effort spent digging into non-financial track records because that’s what makes a good founder. It’s not just, “I was the number seven employee at Uber, so now I’m considered like a smart person.” It’s not impressive to me. Who went to work for Uber when I was in business school? Like people that couldn’t get a job at any of the top 250 firms. True story.

Maybe I’d have some people off, but that’s the truth. I had no interest in Uber. I went to work for the best bank in the world at the time, the number one fixed income. That was a hard job to get. Uber was when you couldn’t get into Google or Apple or Microsoft or any other good firm. They’re like, “I’ve got to work somewhere. I don’t want to leave the University of Chicago without a bid.” That’s where they went. I don’t know. This is just one of the things I think the market has totally wrong. The other thing I’ll mention in terms of trends is that let’s stop chasing this shiny object.

Extraordinary leadership is the number one criterion that a founder must possess. Share on XThat’s going to change things. Guess what? Ninety-five percent of the investments that people are making today are going to be zeros because they have no idea what they’re investing in. They have no idea what the implications are. They have no idea who they’re who they’re investing in. Everybody that pitches me now has some AI spin. I dig in a little bit and like they fall flat on their face. They have no AI chops. They have no idea what AI is. They’re just BS artists. They’re peddling crap. I think that’s another thing that people need to think about.

I wouldn’t say Craig and I ignore the sector, but we are agnostic. We believe and we’ve seen with the founders that we backed that they’ll understand and see what’s happening with the changes in the technologies in the marketplace and adjust accordingly. It’s not a full bet on a specific technology or a specific sector. How can we add value? Is this founder somebody who’s solving a real problem and understanding how they plan to build the business against it?

We try to come in late seed, so there’s something there to evaluate. Pricing is not always complete. Certainly, all the entire services or products aren’t complete. The team is not completely baked, but there’s enough there for us to sink our teeth into it, and understand the assumptions and how that founding team thinks about solving the problem. You can see a little bit of perseverance and coachability in those components.

I agree. AI may be a little different. Even in our existing current portfolio, AI is impacting. How do you increase efficiency? Where do you use it most usefully? You be competitive and still be able to use that tool effectively. That’s a piece of it. It’s not the whole thing. It’s like, “We’re turning into a complete AI focus shop with no expertise or knowledge about it. I think that is a recipe for disaster.

Common Mistakes By Investors

This segues nicely into my next question, which is what are the common mistakes that you see investors making? VCs, that is. You could also say institutional investors too in terms of how they’re allocating.

Any institution that didn’t invest in Moonshots? I can speak personally. I’ve been investing since 2004. While we were running the syndicate, we went angel investing from 2004 to 2014, so a decade of angel investing. From 2014 to 2017, we had a syndicate vehicle only. In 2017, we raised for fund 1, 2020 for fund 2, and we’re in fund 3 now. A little Malcolm Gladwell here. Every time I ignore that gut feeling, I was burned every single time.

Craig and I have to agree when we make an investment, like we both have to say yes. We can both be persuasive with the other one if somebody’s not completely feeling it. We’ve helped each other to make the right decision by acting that way. I invested in a founder where something just wasn’t quite right. They came out of a gust program, like a named program that everybody knows, so I’m not going to say it. They had all the right bells and whistles. It was in a space that seemed like it was pretty hot at the time, but I could never pin down the founder.

This was in the syndicate before we got to formalize the fund component. Something was off, like I couldn’t quite get it. We did a medium-sized syndicate into them with the rest of a whole bunch of other people who invested. The next thing is skiing in the Alps on their Instagram and then going to the Bahamas. Updates are very sporadic without relevant information on being able to figure out what does that means for burn. Most founders now that worked with us, when they first talked to me or see me, they tell me what’s in the bank and what the number of burn months is.

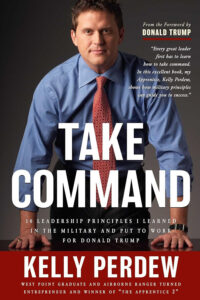

Take Command: 10 Leadership Principles I Learned in the Military and Put to Work for Donald Trump

That’s the first thing they say. I know they’re thinking about it, too, but that’s like you have to stay alive. Your number one job is to keep cash in the bank. It eventually dissipated and we lost. It wasn’t huge, but it was still like, “I’m never ignoring that gut feeling again. Never happening.” I think people can get caught up in hype and we saw that that definitely occurred where it’s like, “I don’t even have to do any due diligence. How do I get my money into this deal?” That’s when it gets really scary and, notwithstanding, legal fiduciary responsibilities. That’s just not a way to operate.

I’m with you when it comes to the founder’s integrity, if you will. One of the things I always like to do is check out how they’re living their personal life. If I show up at their office and they’ve got like a $500,000 automobile and they haven’t yet reached profitability, there’s no way I’m investing with them. In fact, nobody I know will invest with them if I have anything to do with it. My view is they need to be grinders. They need to basically put their investors first. After they’ve made money for their investors, they can do whatever the heck they want.

They also need to be accessible and transparent. To your point earlier, you’re trying to reach somebody to get insights on the business and they’re on the ski slopes, that’s a non-starter. It’s like simple things. People ask, “How do you invest successfully in early-stage companies that don’t have a long track record, that don’t have a ton of assets?” It’s like, “You have to look where others don’t.” You have to have some rules and processes around that. It’s not just, “Do I like this person and do I feel like I can trust them?”

I think there’s a lot to be said for having processes that attempt to quantify things that aren’t usually that easy to quantify. Their personality types. Are they humble? Are they hardworking? Do they have high integrity? Can you trust them? Are they putting you first? Are they unselfish? How does their team respond to them as well? That’s the other thing I like to look at. It is not just the leadership team, but that second layer of folks at the firm. I want to see who they are hiring. If I walk into a startup’s office and they’ve got five good-looking receptionists that aren’t doing anything, again, bad use of cash.

I see that a lot or not as much anymore because that’s not as acceptable. Even in 2021, a lot of startups were using their investor cash for things that weren’t adding value to the business. You really get a sense of a lot of that until you have boots on the ground. Despite this Zoom business economy now, this work-from-home, the reality is if you don’t know somebody, you haven’t gotten to see their facilities on site and you haven’t gotten to meet their team, then you’re probably not making an informed decision.

Completely agree. The due diligence is critical. We focus on leadership. I wrote a book on applying ten leadership principles from the military to business so we can evaluate our founders. In some cases, subjectively, in other cases, objectively across those ten principles, the team is critical. I’ve never seen a great leader who didn’t bring people with her or him. It’s not like a one-person show. They’ve got a following because they’ve built that leadership doesn’t exist in this one instance. It’s a leadership quality.

When they go into this role or found this company, hearing that founder story, that origin story is incredibly important. We’ll get introduced by our co-investors, later-stage investors who know what we like and we’ve worked with previously as our companies grow into them, and send us deals. The founders are invariably like, “Where would you like me to start?” I’m like, “I’m investing in your C Brown if I invest.” That is not the end of the story. I need to hear how compelling you are and are going to be when you’re raising a series C.

You need to blow me away from that first presentation, but the origin story, why it’s important, how big can it get? Why are you differentiated? All these critical elements that I need to see and hear. I need to feel the passion. I need to understand impeccability. You need to know the details of your financial model. You, the founder. One thing that we have to coach because it’s not as obvious is that as much as they’re hated and dreaded fundraising, you have to know the docs. That’s where everything happens.

You need to know all of the provisions and your attorney that you’re already paying will describe to you all the elements, but you need to become an expert on the financial docs, not defer to an attorney who has twenty deals they’re working on at some time, because that’s your business, that’s your baby. Saying that to somebody and then three weeks later, them still not understanding terms, means they’re not coachable, they’re not listening. There are a whole bunch of feedback loops where we can understand how these founders are over a longer period of time.

People can get caught up in the hype. That’s when it gets scary. Share on XI think when it comes to docs, people should really work through them themselves first and you really bring in the lawyers at the last minute after you’ve already determined what you need and then have the lawyer look through it to make sure that you’re protected and point out any things you may have missed.

I think a big mistake for a lot of folks is they bring in lawyers too soon and they rely on them too heavily. My view is I do all my own docs initially. Granted, I have a background in structuring. I have a structure to do a million different actions, but I don’t bring in the lawyers until the very end. I’m like, “I’m not going to pay you so that I can do your work for you.” I’m going to basically figure it all out, have a discussion with the counterparty. We’re going to agree on everything. The lawyer is going to paper up what we’ve already agreed to. Lawyers don’t negotiate.

Call out something technical that could get you in jeopardy. This is my advice to the founders that we work with, it’s like you can get death by a thousand cuts from an attorney who’s doing everything zealously to protect your position. The best attorneys I’ve worked with listened to me describe the business solution I wanted and then created the structure around that solution but gave me fair warnings about the places where we might have exposure. When I say go, there’s no more discussion. I got it, I’ve taken that into account. It’s documented. Now, let’s get the deal done. Those are the best attorneys, in my opinion, that I’ve worked with.

They need to have business sense. They need to be commercial and understand what are my goals and what are the goals of my counterparty. Make sure that I’m protected in that business context. If they’re just going into it as a lawyer, they can nitpick a document all day long and they’ll probably spend tens of thousands of your dollars and stuff that doesn’t even matter. In fact, it might not even help you because let’s not forget, when you’re having those negotiations, that’s either building the relationship or it’s taking away from the relationship.

I always think that if I’m going to hire somebody or somebody wants to partner with me, I’m going to judge them in large part on how those negotiations go. If they’re pain-in-the-ass to deal with at the outset, then why would I want to partner with them? It’s like, “We’re trying to be fair here. We’re trying to create value for both of us. We should be able to do that. If it’s overly complicated or you need to nitpick every little detail, then you’re just not somebody I want to do business with.”

Venture Debt For Founders

A couple more questions here. One is I want to talk about venture debt because we’ve been talking a lot about the need for capital. Venture debt is something that’s not necessarily well understood by a lot of founders or investors for that matter. Essentially, venture debt is debt capital for venture-backed companies that have already reached a stage where they’re generating revenue, typically, and they can service the debt and they’re looking for growth capital. They want capital that’s less dilutive than equity financing, that’s cheaper than equity financing, and that’s faster to obtain.

There’s always been a need for venture debt, but I think it’s become much more relevant recently because there are more companies than ever before that need capital. They’re not able to raise equity capital effectively. They either get it at all or it’s really expensive, or it takes too long to get. They’re looking on the debt side. Of course, we had Silicon Valley Bank collapse.

Although they’re technically in the market for citizens, their shells, their former selves, I don’t think that business is going to be more than probably 20% of the original footprint when all is said and done. There’s a lack of capital and a lot of demand for capital. There’s this big disconnect there, which creates an opportunity for venture lenders, specifically non-bank venture lenders. I wanted to get your thoughts as a VC who’s worked with many portfolio companies, how should founders be thinking about venture debt?

Venture Capital: Venture debt is a valuable tool that a founder should know and understand how to access and utilize.

My experience with venture debt is it’s an incredibly valuable tool that a founder should know and understand how to access, utilize. Similarly to what we discussed on understanding the legal documents, get a handle on understanding how payback works when it turns on, what it does to cashflow? I think that’s probably the biggest warning I would have for anybody who is an extra $5 million, $20 million, $100 million, whatever it might be, really understanding the parameters and what that does to your cashflow is critical, which requires a good finance function if you don’t have those chops yourself as the founder.

It can be incredibly valuable for the current ecosystem and the need to extend the runway for all the reasons you mentioned. You caveated, which can be a great tool for a company that’s generating revenue, I know a lot of companies were able or got to or did take on venture debt when they weren’t necessarily generating revenue. If you don’t have a good handle on understanding on how your revenue is really going to ramp, which you can never know if you don’t even have it turned on yet, it’s literally anyone’s guess on what’s going to happen.

I think it’s a little more dangerous to do that. I think for growth capital, awesome, and incredibly important. It gets a little scarier when you’re funding payroll. Knowing a low watermark on cash relative to debt is super important. If you’ve got a trajectory or projection on how you’re going to pull up into the profitability component, it’s super important. For someone who has excellent financial controls in place and some predictability on revenue, I don’t want to say free money, because it’s not free, but it’s a phenomenal tool that I think all founders should evaluate. We ensure that we evaluate it in every deal that we’re doing.

When founders are looking to raise venture debt, what are the options that you typically discuss with them in terms of how they might find the right providers?

Debt, like equity, there’s a spectrum. What we discussed previously about reputation is critically important. Frequently, the debt providers have relationships actually with the VCs because historically, there’s like a look across the table and an unwritten agreement that you’re good for this if the company doesn’t make it dynamic even though it’s not legally constructed that way typically, especially on those that hadn’t hit revenue yet. What additional value can that debt provider add, whether it’s additional relationships or banking relationships in other areas?

There are other elements to it that are very similar to any vendor, including if you consider a VC or vendor. How else are you going to add value? How trustworthy are you? There are regulatory guidelines that are associated with debt that are not associated with equity. It’s a very serious business and a very serious deal and you need to understand all those parameters. Debt covenants are real and in the same way, you need to understand your legal docs for financing. You need to understand any debt structure and the parameters of the covenants around any debt financing.

It’s funny because we get a lot of inbound from companies that aren’t at all fit because they’re basically looking to raise debt capital because they raise equity capital. I think one of the misconceptions is that venture debt is there to help companies that are struggling. That’s actually the furthest thing from the truth. The reality is, to your point earlier, that venture debt is growth capital for successful companies that already have revenue.

At least that successful venture lenders, like that’s what they do. At ARI, we would never land more typically than 50% against recurring revenue. If a company is doing $20 million a year revenue, we’d make them potentially $10 million loan. Companies doing $2 million revenue, it’s a non-starter because the minimum we’re going to look for is probably $10 million on the low end. If that’s a very different type of company than a lot of the folks that are out there who are hearing about venture debt and they’re like, “This is a way for me to keep my business from going under.”

The best attorneys listen to the business solution you want and create a structure around that. Share on XUnfortunately, that’s not what venture debt is. There are lenders that do that, but it’s going to be really expensive. Quite frankly, those are not what I call venture lenders. Those are lenders that are lending to distressed companies. I mean, a couple of metrics that I think people should know in terms of how to size venture debt for their own companies. Typically, you need to have some revenue. Every bank’s different and every non-bank lender is different in terms of their metrics, but at ARI, we’re looking for a minimum of $10 million in revenue.

Typically, you want to have more than that, but that’s the minimum. Don’t want to lend more than 50% against annual revenue. I keep the loan to value less than 20%. Most of the deals that we’re looking at now in our pipeline are single-digit LTVs. It’s called like 7% to 10% range. Just to put that in context, the good lenders that have performed well through cycles typically have an LTV in that mid-teens range.

One of the top private lenders had an average LTV of 12% for their portfolio. A couple of the leading business development companies that are publicly traded have LTVs and they’re like their mid-teens, like 16% or so. That’s key for lenders. Also make sure that the equity capital is there, too. Traditionally venture debt comes in after the company’s raised equity capital. Think of it as a runway extension, additional capital at a lower cost. Decreases your weighted average cost of capital, but it’s not there as a standalone product. It’s almost always done in conjunction with an equity raise.

Typically, 3 to 6 months after that equity raise where, the company realizes, “We could go raise some more capital and we probably should.” For all the reasons we were talking about earlier. If you want to raise some more capital, really decrease your business risk in the sense that you’ve got an extra. You have six months of runway from this debt. That’s the ideal situation where a company saying, “We’re raising $50 million total, we’re doing $40 million in equity and we’ll do $10 million in debt.”

That means we’re getting $10 million of lower-cost capital, much less dilutive. That’s a win and also extends our runway a bit as well. There are other uses for venture debt as well that are more specific based on the situation like you could use it as bridge capital. For the most part, it’s best suited for companies that are just looking for additional growth capital. It’s basically cheaper money for winners, not bailout money for losers.

Investing In Innovation

That’s the way I think about it. The last question for you is, how should investors think about investing in innovation over the next three to five years? If you’re an institutional investor, you’re like a big pension or an endowment or a large family office, and you’ve got some money you put to work in the innovation economy, what are the themes you should be thinking about and how should you be thinking about allocating?

I think that the institutions, obviously, upstream from where we are that you just asked about, but the themes are the same. Health is huge, space is huge, how AI impacts. When we see new technologies like AI, we think about picks and shovels rather than an individual niche, hopefully hitting the exact right play of an AI play. Things that enable AI and/or cause AI, like GPUs for AI and the impact on Nvidia. What does that mean? What does the infrastructure have to be to support additional items like that?

When the economy starts to falter, everybody goes running to the government side. That’s why dual use has come on so strong. Craig and I had been doing it for many years. Now, it’s really interesting to every VC who’s never had anything to do with it. Not every VC, but it’s become a little bit more mainstream. I’m glad for that because I think anything that helps increase the security of the nation and helps the United States is phenomenal. I’m glad for it, but if you’re an allocator at an institutional level, you want to look for the same thing we looked for, which is extraordinary leadership and leaning into those categories.

Not being wedded to a specific technology. The technology has shown shifts so quickly that 10-year and 20-year, 30-year cycles of investing in a very specific technology versus a sector and/or the leadership in that sector will increase the likelihood of your results. I think in the same way. I’m looking at a founder and saying, “Do I want to spend the next 7 to 12 years of my life on speed dial with this person?”

Venture Capital: Investing in a very specific technology versus a sector will increase the likelihood of your results.

It’s got to be the right mix for how they’re thinking about it. I realize that institutional LPs have a little different relationship with their brand than Craig and I do with Moonshots in terms of economic incentive, the brand being people that are doing it, but they still have long-term career plans and have their performance shows well.

I think that maybe trying to be a little more entrepreneurial, like you said, the person who’s in Sequoia, what are they on now? Forty-something, I don’t know how many vintages there’ve been, but there’s been a lot. It’s because they’re a storied brand who helped build Silicon Valley. Part of their job should also be thinking about optionality for finding who’s going to be in the Sequoia for twenty years from now or some equivalent. They have a little bit of an eyedropper funding problem. There’s so much money that they deploy.

It’s hard for them to take $5 million optionality and still be able to do diligence and understand and look at all those. They want to be able to deploy $500 million chunks, not $10 or $20 or $30 million chunks. It gets a little more difficult for them to get down what I call the eyedropper funding problem. For those who are able to do that and analyze the same way we’re looking at 2,000 deals, you’re going to be able to create extraordinary returns for your investor base. I would like to do that for the Fireman’s Fund. I would like to do that for pick your pension plan. That’s the people who’ve worked really hard to get where they are and expecting to have fantastic returns come out of that.

It’s been great having you on, Kelly. I really appreciate your time and love the way you’re thinking about the business and how to invest in innovation. I think you’re doing it in a way that makes a lot of sense and really stands out in that regard.

Thank you, Zack. I look forward to steering our founders over to you for venture debt when they’re appropriately positioned.

I appreciate that. I’ll see you soon in person, I’m sure. I really appreciate you coming on and love what you and Craig have built at Moonshots. Thanks, everybody, for reading. This episode featured Kelly Perdew, the man, the myth, the legend, and the best investor in innovation. See you all next time.

Important Links

- Zack Ellison on LinkedIn

- Applied Real Intelligence (A.R.I.)

- 7 in 7 Show with Zack Ellison on Apple

- 7 in 7 Show with Zack Ellison on Spotify

- 7 in 7 Show with Zack Ellison on YouTube

- 7 in 7 Show with Zack Ellison on Amazon Music

- Kelly Perdew on LinkedIn

- Moonshots Capital

- Kelly Perdew

- Take Command: 10 leadership principles I learned in the Military and Put to Work for Donald Trump

- Kelly Perdew on Twitter

- 7 in 7 Show Disclaimer

About Kelly Perdew

Kelly is the CEO of Fastpoint Games. Fastpoint Games is a leading developer of live, data-drive games that enable clients to engage, reward and monetize their users. Fastpoint Games leverages an award-winning, proprietary cloud-based platform to deliver clients customized games and integrated gaming solutions across any channel and around any set of structured data. The games-as-a-service model enables marketers, in virtually any industry, to offer their users an engaging, quality game experience quickly, without taxing their company’s resources. Fastpoint Games is privately held, and based in Los Angeles, CA. Investors include Allen & Co, Mission Ventures, DFJ Dragon and Sports Capital Partners Worldwide.

Kelly is the CEO of Fastpoint Games. Fastpoint Games is a leading developer of live, data-drive games that enable clients to engage, reward and monetize their users. Fastpoint Games leverages an award-winning, proprietary cloud-based platform to deliver clients customized games and integrated gaming solutions across any channel and around any set of structured data. The games-as-a-service model enables marketers, in virtually any industry, to offer their users an engaging, quality game experience quickly, without taxing their company’s resources. Fastpoint Games is privately held, and based in Los Angeles, CA. Investors include Allen & Co, Mission Ventures, DFJ Dragon and Sports Capital Partners Worldwide.

Kelly was previously the President of ProElite.com; an online social network that provides tools for combat sports enthusiasts. While Kelly was there, ProElite, Inc. raised over $40M, including $5M from CBS, and inked a 3-year exclusive deal with Showtime for airing its mixed martial arts (”MMA”) fights and televised the first network primetime MMA fight on CBS.

Kelly has held numerous leadership positions in such companies as CoreObjects Software; MotorPride.com, K12 Productions, and eteamz.com. Kelly was the President of the largest amateur sport portal on the web – eteamz.com – and helped build the company which is now serving more than 3.2 million amateur sports teams as part of Active Networks. Kelly was a Manager at Deloitte Consulting in the Braxton Strategy Practice and served in the US Army as a Military Intelligence Officer and Airborne Ranger.

After winning the second season of the NBC hit show, The Apprentice, Kelly spent 2005 as an Executive Vice President in the Trump Organization, where he managed several projects. Kelly earned a BS from the US Military Academy, West Point, a JD from the UCLA School of Law, and an MBA from the Anderson School at UCLA. Kelly authored, “TAKE COMMAND: 10 Leadership Principles I Learned in the Military and Put to Work for Donald Trump,” to provide guidance on how anyone can develop their leadership capabilities and he donates a percentage of the royalties to the USO.

Kelly is a nationally recognized speaker on leadership, technology, career development and entrepreneurship. He hosted a show on the Military Channel called “GI Factory” that looks at innovative military technologies and takes the viewer into the US factories where they are made and tracks them from raw materials to completed product. He is a celebrity spokesperson for Big Brothers/Sisters and The National Guard Youth Challenge Program. Kelly received a Presidential Appointment to the President’s Council on Civic Participation and Service in June 2006.